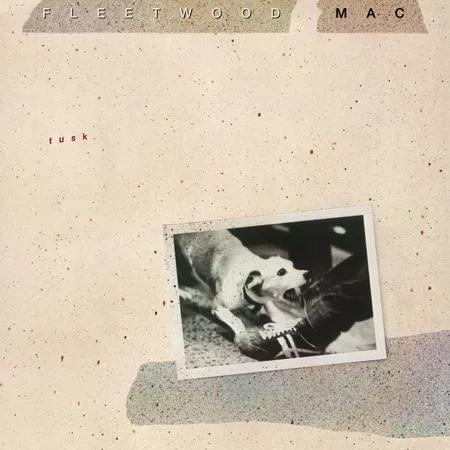

45 Years Later, Tusk is still the most overlooked Fleetwood Mac record

The year was 1979, and Fleetwood Mac was still taking in the massive success of their record Rumours, released in 1977. Their label, Warner Bros., was thrilled at the traction that Rumours gained and pushed for them to stick to that sound. But Tusk, the record that they released October 12th, 1979, sounded nothing like Rumours—in fact, it sounded nothing like what they had ever made before. To the total dismay of label executives, Tusk ended up being a complete commercial failure. Not only did it cost significantly more to make than Rumours did (at the time, it was the most expensive rock album ever recorded), it also generated far less revenue. But what made this album so commercially unsuccessful, and why did the band opt to go in a different direction from their biggest hit?

First and foremost, Tusk was an act of rebellion. Fleetwood Mac’s rising frontman, Lindsay Buckingham, wanted more than anything to create an album that subverted everyone’s expectations of the band. Buckingham had been experimenting in his home studio, increasingly inspired by the new post-punk sounds that emerged out of the late ‘70s. While the rest of the band wasn’t as committed to this new direction, they initially thought it couldn’t hurt to have Buckingham do his thing on Tusk. Mick Fleetwood, the band’s eccentric drummer and previous frontman, decided that it would need to be a double album, considering the high volume of output of the band’s three main songwriters: Buckingham, Stevie Nicks, and Christine McVie.

So Tusk, the band’s most experimental album up until that point, was born after ten grueling months in the studio. Those who were in the studio with the band at the time described the atmosphere as hostile (just as it was during the recording of Rumours), with Ken Calliat, the band’s producer, recalling that Buckingham was a “maniac”. These studio sessions produced a whopping 20 songs, with the album lasting just under 1 hour and 15 minutes.

Once Tusk was released, it became clear that this experimentation wasn’t financially fruitful. The band became increasingly torn apart, with members pointing their fingers at Buckingham for “going too far” with his insistence on transforming Fleetwood Mac’s sound. Meanwhile, the press had conflicting takes on whether the record was a success or not. Some critics describe Tusk as fragmented, lazy, and unoriginal, while others consider it to be a groundbreaking and innovative record. Differences aside, both those who hated and loved Tusk could agree on one thing: it was weird. While it gained more attention and praise recently, its reputation of weirdness overshadows the creative ingenuity that I believe makes it one of the greatest rock records of all time.

John McVie, the band’s bassist, said that Tusk sounds like the work of three solo artists rather than a cohesive project by a well-established band. But it is precisely this quality that made fans of the album (myself included) love it so much. The entire record is a push and pull between Fleetwood Mac’s three songwriting powerhouses, and it's a fascinating quality to bear witness to. Each songwriter shines brightly and distinctly, even if it comes at the cost of a lack of unity. Buckingham’s bizarre experimentation is juxtaposed with Christine McVie’s signature love ballads and Stevie Nicks’s powerful, witchy tunes, which we first heard with the band’s self-titled record. The placement of the songs on the album is crucial: right after listeners recover from the rollercoasters that Buckingham takes us on, we find ourselves comforted by McVie’s soothing vocals or the familiarity of the dreamy, trance-like songs written and performed by Nicks. The songs’ placements are evidence that there is some cohesion in the chaos that is Tusk. Some critics of the album find the dramatic differences between the album’s opening track, “Over and Over” (which sounds like it could have been a Rumours B-side) and the subsequent fast-paced, punk-influenced track, “The Ledge,” to be quite jarring. However, I think the pairing of these two initial tracks excellently sets the stage for the rest of the record’s energy- a constant back-and-forth reflective of a turbulent time for the band.

Aside from the chaos, there is so much more to love about Tusk. It is an emotionally intense record, but not in the same way Rumours was. If the dominant emotion throughout Rumours was anger, then Tusk was a manifestation of the lingering bitterness and resentment in the aftermath of the storm. Additionally, Tusk features some of my all-time favorite Fleetwood Mac songs, such as “Sara,” a mystical, intriguing tune written by Nicks, “Storms,” a stripped-down breakup ballad also written by Nicks, “Brown Eyes,” my favorite songwriting from McVie, and “I Know I’m Not Wrong,” a punchy country jam (featuring some sick harmonica) written by Buckingham. And then of course, there is the eclectic titular track featuring a full marching band, per the request of Mick Fleetwood. The entire record is sonically interesting, and the credit cannot solely be given to Buckingham and his experimentation.

Tusk is not the only example of a rock band choosing to go the experimental route after the release of their most successful record. The Beatles did it with their self-titled record (“The White Album”) and Radiohead did it with Kid A. Yet Tusk is the only one that seems to go largely unrecognized in discussions about the legacy the band leaves behind. As a longtime fan of Fleetwood Mac (we’re talking since the single digits!), Tusk has crept all the way up to the top of my ranking of their records, and it amazes me that 45 years after its release most people just consider it to be a strange blip in their impressive discography. Tusk should be appreciated for more than what it means in relation to Fleetwood Mac’s hits. It is a record bursting with creative genius and a brave attempt at doing what music is all about—daring to find new ways to express oneself.

Listen to Tusk here